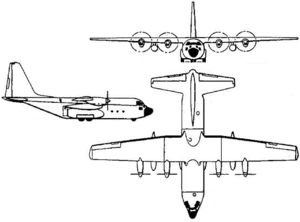

Lockheed C-130 Hercules

| C-130 Hercules | |

|---|---|

|

|

| USAF C-130E | |

| Role | Military transport aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Lockheed Martin |

| First flight | 23 August 1954 |

| Introduced | December 1957 |

| Status | In production, in service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force United States Marine Corps Royal Air Force others in Operators |

| Number built | 2,262 as of 2006[1] |

| Unit cost | US$62 million |

| Variants | C-130J Super Hercules AC-130 Spectre/Spooky Lockheed DC-130 Lockheed EC-130 Lockheed EC-130E Rivet Rider Lockheed HC-130 Lockheed LC-130 Lockheed MC-130 Lockheed WC-130 Lockheed L-100 Hercules |

The Lockheed C-130 Hercules is a four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft designed and built originally by Lockheed, now Lockheed Martin. Capable of using unprepared runways for takeoffs and landings, the C-130 was originally designed as a troop, medical evacuation, and cargo transport aircraft. The versatile airframe has found uses in a variety of other roles, including as a gunship (AC-130), for airborne assault, search and rescue, scientific research support, weather reconnaissance, aerial refueling, maritime patrol and aerial firefighting. It is the main tactical airlifter for many military forces worldwide. Over 40 models and variants of the Hercules serve with more than 60 nations.

During its years of service the Hercules family has participated in countless military, civilian and humanitarian aid operations. The family has the longest continuous production run of any military aircraft in history. In 2007, the C-130 became the fifth aircraft—after the English Electric Canberra, B-52 Stratofortress, Tupolev Tu-95, and KC-135 Stratotanker—to mark 50 years of continuous use with its original primary customer, in this case, the United States Air Force. The C-130 is also the only military aircraft to remain in continuous production for 50 years with its original customer, as the updated C-130J Super Hercules.

Contents |

Design and development

Background and requirements

The Korean War, which began in June 1950, showed that World War II-era transports—C-119 Flying Boxcars, C-47 Skytrains and C-46 Commandos—were inadequate for modern warfare. Thus on 2 February 1951, the United States Air Force issued a General Operating Requirement (GOR) for a new transport to Boeing, Douglas, Fairchild, Lockheed, Martin, Chase Aircraft, North American, Northrop, and Airlifts Inc. The new transport would have a capacity for 92 passengers, 72 combat troops or 64 paratroopers in a cargo compartment that is approximately 41 feet long, 9 feet high, and 10 feet wide. Unlike transports derived from passenger airliners, it was designed from the ground-up as a combat transport with loading from a ramp at the rear of the fuselage. This was first pioneered on the WW II German Junkers Ju 252 and Ju 253 "Hercules" transport prototypes in WWII. The Boeing C-97 also had a retracting ramp through clamshell doors, but could not be used for airdrops of cargo.

The Hercules also resembled a larger 4-engined brother to the C-123 Provider with a similar wing and cargo ramp layout. That plane evolved from the Chase XCG-20 Avitruc which was first designed and flown as a cargo glider in 1947.[2] The rear ramp not only makes it possible to drive vehicles onto the plane (also possible with forward ramp on a C-124), but to airdrop or use low-altitude extraction for Sheridan tanks or even dropping improvised "daisy cutter" bombs.

A key feature was the introduction of the T56 turboprop which was first developed specifically for the C-130. At the time, the turboprop was a new application of jet engines which used exhaust gases to turn a shafted propeller which offered greater range at propeller-driven speeds compared to pure jets which were faster but thirstier. As was the case on helicopters of that era such as the UH-1 Huey, turboshafts produced much more power for their weight than piston engines. Lockheed would subsequently use the same engines and technology in the Lockheed L-188 Electra. That plane was a disappointment as an airliner, but quite successfully adapted as the P-3 Orion patrol plane where speed and endurance of turboprops excelled.

The new Lockheed cargo plane design possessed a range of 1,100 nmi (1,300 mi; 2,000 km), takeoff capability from short and unprepared strips, and the ability to fly with one engine shut down. Fairchild, North American, Martin and Northrop declined to participate. The remaining five companies tendered a total of ten designs: Lockheed two, Boeing one, Chase three, Douglas three, and Airlifts Inc. one. The contest was a close affair between the lighter of the two Lockheed (preliminary project designation L-206) proposals and a four-turboprop Douglas design.

The Lockheed design team was led by Willis Hawkins, starting with a 130 page proposal for the Lockheed L-206.[3] Hall Hibbard, Lockheed vice president and chief engineer, saw the proposal and directed it to Kelly Johnson, who did not care for the low-speed, unarmed aircraft, and remarked, "If you sign that letter, you will destroy the Lockheed Company."[3] Both Hibbard and Johnson signed the proposal and the company won the contract for the now-designated Model 82 on 2 July 1951.[4]

The first flight of the YC-130 prototype was made on 23 August 1954 from the Lockheed plant in Burbank, California. The aircraft, serial number 53-3397, was the second prototype but the first of the two to fly. The YC-130 was piloted by Stanley Beltz and Roy Wimmer on its 61-minute flight to Edwards Air Force Base; Jack Real and Dick Stanton served as flight engineers. Kelly Johnson flew chase in a P2V Neptune.[5]

Production

After the two prototypes were completed, production began in Marietta, Georgia, where more than 2,300 C-130s have been built.[6]

The initial production model, the C-130A, was powered by Allison T56-A-9 turboprops with three-blade propellers. Deliveries began in December 1956, continuing until the introduction of the C-130B model in 1959. Some A models were re-designated C-130D after being equipped with skis. The newer C-130B had ailerons with increased boost—3,000 psi (21 MPa) versus 2,050 psi (14 MPa)—as well as uprated engines and four-bladed propellers that were standard until the J-model's introduction.

C-130A model

The first production C-130s were designated as A-models, with deliveries in 1956 to the 463d Troop Carrier Wing at Ardmore AFB, Oklahoma and the 314th Troop Carrier Wing at Sewart AFB, Tennessee. Six additional squadrons were assigned to the 322d Air Division in Europe and the 315th Air Division in the Far East. Additional airplanes were modified for electronics intelligence work and assigned to Rhein-Main Air Base, Germany while modified RC-130As were assigned to the Military Air Transport Service (MATS) photo-mapping division. Airplanes equipped with giant skis were designated as C-130Ds, but were essentially A-models except for the conversion. Australia became the first non American force to operate the C130A Hercules with 12 examples being delivered during late 1958-early 1959. These aircraft were fitted with 3 blade AeroProducts propeller of 15' diameter. As the C-130A became operational with Tactical Air Command (TAC), the airplane's lack of range became apparent and additional fuel capacity was added in the form of external pylon-mounted tanks at the end of the wings. The A-model continued in service through the Vietnam War, where the airplanes assigned to the four squadrons at Naha AB, Okinawa and one at Tachikawa Air Base, Japan performed yeoman's service, including operating highly classified special operations missions such as the BLIND BAT FAC/Flare mission and FACT SHEET leaflet mission over Laos and North Vietnam. The A-model was also provided to the South Vietnamese Air Force as part of the Vietnamization program at the end of the war, and equipped three squadrons based at Tan Son Nhut AFB. The last operator in the world is the Honduran Air Force, which is still flying one of five A model Hercs (FAH 558, c/n 3042) as of October 2009.[7]

C-130B model

The C-130B model was developed to complement the A-models that had previously been delivered, and incorporated new features, particularly increased fuel capacity in the form of auxiliary tanks built into the center wing section and an AC electrical system. Four-bladed Hamilton Standard propellers replaced the Aero Product three-bladed propellers that distinguished the earlier A-models. B-models replaced A-models in the 314th and 463rd Troop Carrier Wings. During the Vietnam War four squadrons assigned to the 463rd Troop Carrier/Tactical Airlift Wing based at Clark and Mactan Air Fields in the Philippines were used primarily for tactical airlift operations in South Vietnam. In the spring of 1969, 463rd crews commenced COMMANDO VAULT bombing missions dropping M-121 10,000 lb (4,534 kg) bombs to clear "instant LZs" for helicopters. As the Vietnam War wound down, the 463rd B-models and A-models of the 374th Tactical Airlift Wing were transferred back to the United States where most were assigned to Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard units. Another prominent role for the B-model was with the United States Marine Corps, where Hercules initially designated as GV-1s replaced C-119s. After Air Force C-130Ds proved the type's usefulness in Antarctica, the US Navy purchased a number of B-models equipped with skis that were designated as LC-130s. An electronic reconnaissance variant of the C-130B was designated C-130B-II. 13 aircraft were converted and operated under the SUN VALLEY program name. They were operated primarily from Yokota Air Base, Japan. All reverted to standard C-130B cargo aircraft after their replacement in the reconnaissance role by other aircraft. The C-130B-II was distinguished by its false external wing fuel tanks, which were disguised signals intelligence (SIGINT) receiver antennas. These pods were slightly larger than the standard wing tanks found on other C-130Bs. Most aircraft featured a swept blade antenna on the upper fuselage, as well as extra wire antennas between the vertical fin and upper fuselage not found on other C-130s. Radio call numbers on the tail of these aircraft were regularly changed so as to confuse observers and disguise their true mission.

C-130E model

The extended range C-130E model entered service in 1962 after it was developed as an interim long-range transport for the Military Air Transport Service. Essentially a B-model, the new designation was the result of the installation of 1,360 US gal (5,150 L) Sargent Fletcher external fuel tanks under each wings (mid-section) and more powerful Allison T56-A-7A turboprops. The hydraulic boost pressure to the ailerons was reduced back to 2050 psi as a consequence of the external tanks weight in the middle of the wingspan. The E model also featured structural improvements, avionics upgrades and a higher gross weight. Australia took delivery of 12 C130E Hercules during 1966-67 to supplement the 12 C130A models already in service with the RAAF.

C-130F / KC-130F / C-130G models

The KC-130 tankers, originally C-130Fs procured for the US Marine Corps (USMC) in 1958 (under the designation GV-1) are equipped with a removable 3,600 US gal (13,626 l) stainless steel fuel tank carried inside the cargo compartment. The two wing-mounted hose and drogue aerial refueling pods each transfer up to 300 US gal per minute (19 l per second) to two aircraft simultaneously, allowing for rapid cycle times of multiple-receiver aircraft formations, (a typical tanker formation of four aircraft in less than 30 minutes). The US Navy's C-130G has increased structural strength allowing higher gross weight operation.

C-130H model

The C-130H model has updated Allison T56-A-15 turboprops, a redesigned outer wing, updated avionics and other minor improvements. Later H models had a new, fatigue-life-improved, center wing that was retro-fitted to many earlier H-models. The H model remains in widespread use with the US Air Force (USAF) and many foreign air forces. Initial deliveries began in 1964 (to the RNZAF), remaining in production until 1996. An improved C-130H was introduced in 1974, with Australia purchasing 12 of type in 1978 to replace the original 12 C130A models which had first entered RAAF Service in 1958.

The United States Coast Guard employs the HC-130H for long range search and rescue, drug interdiction, illegal migrant patrols, homeland security, and logistics.

C-130H models produced from 1992 to 1996 were designated as C-130H3 by the USAF. The 3 denoting the third variation in design for the H series. Improvements included ring laser gyros for the INUs, GPS receivers, a partial glass cockpit (ADI and HSI instruments), a more capable APN-241 color radar, night vision device compatible instrument lighting, and an integrated radar and missile warning system. The electrical system upgrade included Generator Control Units (GCU) and Bus Switching units (BSU)to provide stable power to the more sensitive upgraded components.

C-130K model

The equivalent model for export to the UK is the C-130K, known by the Royal Air Force (RAF) as the Hercules C.1. The C-130H-30 (Hercules C.3 in RAF service) is a stretched version of the original Hercules, achieved by inserting a 100 in (2.54 m) plug aft of the cockpit and an 80 in (2.03 m) plug at the rear of the fuselage. A single C-130K was purchased by the Met Office for use by its Meteorological Research Flight, where it was classified as the Hercules W.2. This aircraft was heavily modified (with its most prominent feature being the long red and white striped atmospheric probe on the nose and the move of the weather radar into a pod above the forward fuselage). This aircraft, named Snoopy, was withdrawn in 2001 and was then modified by Marshall of Cambridge Aerospace as flight-test bed for A400M turbine, the TP400. The C-130K is used by the RAF Falcons for parachute drops. Three C-130K (Hercules C Mk.1P) were upgraded and sold to the Austrian Air Force in 2002.[8]

Later C-130 models & variants

The MC-130E Combat Talon was developed for the USAF during the Vietnam War to support special operations missions throughout Southeast Asia, and spawned a family of special missions aircraft. 37 of the earliest models currently operating with the United States Special Operations Command are scheduled to be replaced by new-production MC-130J versions. The EC-130 and EC-130H Compass Call are versions also used by Special Operations.

The HC-130P/N is long range search and rescue variant used by the USAF (to include the Air Force Reserve Command and the Air National Guard) that was developed from the earlier HC-130P. Equipped for deep deployment of Pararescuemen (PJs), survival equipment, and aerial refueling of combat rescue helicopters, HC-130s are usually the on-scene command aircraft for combat SAR missions. Early versions were equipped with the Fulton surface-to-air recovery system, designed to pull a person off the ground using a wire strung from a helium balloon. The John Wayne movie The Green Berets features its use. The Fulton system was later removed when aerial refueling of helicopters proved safer and more versatile. The movie The Perfect Storm depicts a real life SAR mission involving aerial refueling of a New York Air National Guard HH-60G by a New York Air National Guard HC-130P.

The C-130R and C-130T are US Navy and USMC models, both equipped with underwing external fuel tanks. The USN C-130T is similar, but has additional avionics improvements. In both models, aircraft are equipped with Allison T56-A-16 engines. The USMC versions are designated KC-130R or KC-130T when equipped with underwing refueling pods and pylons and are fully night vision system compatible.

The RC-130 is a reconnaissance version. A single example is used by the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force, the aircraft having originally been sold to the former Imperial Iranian Air Force.

The Lockheed L-100 (L-382) is a civilian variant, equivalent to a C-130E model without military equipment. The L-100 also has 2 stretched versions.

Next generation

In the 1970s, Lockheed proposed a C-130 variant with turbofan engines rather than turboprops, but the US Air Force preferred the takeoff performance of the existing aircraft. In the 1980s, the C-130 was intended to be replaced by the Advanced Medium STOL Transport project. The project was canceled and the C-130 has remained in production.

In the 1990s, the improved C-130J Super Hercules was developed by Lockheed (later Lockheed Martin). This model is the newest version and the only model in production. Externally similar to the classic Hercules in general appearance, the J model has new turboprop engines, six-bladed propellers, digital avionics, and other new systems.

Improvements and upgrades

In 2000, Boeing was awarded a US$1.4 billion contract to develop an Avionics Modernization Programme kit for the C-130. The program was beset with delays and cost overruns until project restructuring in 2007.[9] On 2 September 2009, Bloomberg news reported that the planned Avionics Modernization Program (AMP) upgrade to the older C-130s would be dropped to provide more funds for the F-35, CV-22 and airborne tanker replacement programs.[10] However, in June 2010, the Pentagon approved funding for the initial production of the AMP upgrade kits.[11][12] Under the terms of this agreement, the USAF has cleared Boeing to begin low-rate initial production (LRIP) for the C-130 AMP. A total of 198 aircraft are expected to feature the AMP upgrade. The current cost per aircraft is US$14 million although Boeing expects that this price will drop to US$7 million for the 69th aircraft.[9]

Operational history

The Hercules holds the record for the largest and heaviest aircraft to land on an aircraft carrier.[13] In October and November 1963, a USMC KC-130F (BuNo 149798), bailed to the US Naval Air Test Center, made 29 touch-and-go landings, 21 unarrested full-stop landings and 21 unassisted take-offs on the USS Forrestal at a number of different weights.[14] The pilot, LT (later RADM) James Flatley III, USN, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in this test series. The tests were highly successful, but the idea was considered too risky for routine "Carrier Onboard Delivery" (COD) operations. Instead, the C-2 Greyhound was developed as a dedicated COD aircraft. The Hercules used in the test, most recently in service with Marine Aerial Refueler Squadron 352 (VMGR-352) until 2005, is now part of the collection of the National Museum of Naval Aviation at NAS Pensacola, Florida.

While the C-130 is involved in cargo and resupply operations daily, it has been a part of some notable offensive operations:

In 1964 C-130 crews from the 6315th Operations Group at Naha AB, Okinawa commenced FAC/Flare missions over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos supporting USAF strike aircraft. In April 1965 the mission was expanded to North Vietnam where C-130 crews led formations of B-57 bombers on night reconnaissance/strike missions against communist supply routes leading to South Vietnam. In early 1966 Project BLIND BAT/LAMPLIGHTER was established at Ubon RTAFB, Thailand. After the move to Ubon the mission became a four-engine forward air controller (FAC) mission with the C-130 crew searching for targets then calling in strike aircraft. Another little-known C-130 mission flown by Naha-based crews was COMMANDO SCARF, which involved the delivery of chemicals onto sections of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos that were designed to produce mud and landslides in hopes of making the truck routes impassable.

In November 1964, on the other side of the globe, C-130Es from the 464th Troop Carrier Wing but loaned to 322nd Air Division in France, flew one of the most dramatic missions in history in the former Belgian Congo. After a Congolese rebel group named "Simba" took whites in the city of Stanleyville hostage, the US and Belgian developed a joint rescue mission that used the C-130s to airlift and then drop and air-land a force of Belgian paratroopers to rescue the hostages. Two missions were flown, one over Stanleyville designated as RED DRAGON/DRAGON ROUGE and another over Paulis called BLACK DRAGON/DRAGON NOIR during Thanksgiving weeks.[15] The headline-making mission resulted in the first award of the prestigious MacKay Trophy to C-130 crews.

In October 1968 a C-130B from the 463rd Tactical Airlift Wing dropped a pair of M121 10,000 pound bombs that had been developed for the massive B-36 bomber but had never been used. The US Army and US Air Force resurrected the huge weapons as a means of clearing landing zones for helicopters and in early 1969 the 463rd commenced Commando Vault missions. Although the stated purpose of COMMANDO VAULT was to clear LZs, they were also used on enemy base camps and other targets.

The MC-130 Combat Talon variant carries and deploys the among the largest conventional bombs in the world, the BLU-82 "Daisy Cutter" and GBU-43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast bomb, also known as the MOAB. Daisy Cutters were used during the Vietnam War to clear landing zones and to eliminate mine fields. The weight and size of the weapons make it impossible or impractical to load them on conventional bombers. The GBU-43/B MOAB is a successor to the BLU-82 and can perform the same function, as well as perform strike functions against hardened targets in a low air threat environment.

The AC-130 also holds the record for the longest sustained flight by a C-130. From 22 October to 24 October 1997, two AC-130U gunships flew 36.0 hours nonstop from Hurlburt Field Florida to Taegu (Daegu), South Korea while being refueled 7 times by KC-135 tanker aircraft. This record flight shattered the previous record longest flight by over 10 hours while the 2 gunships took on 410,000 lb (190,000 kg) of fuel. The gunship has been used in every major U.S. combat operation since Vietnam, except for Operation Eldorado Canyon, the 1986 attack on Libya.[16]

In the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, the Pakistan Air Force modified/improvised several aircraft for use as heavy bombers, and attacks were made on Indian bridges and troop concentrations with some successes. No aircraft were lost in the operations, though one was slightly damaged.[17]

It was also used in the 1976 Entebbe raid in which Israeli commando forces carried a surprise assault to rescue 103 passengers of an airliner hijacked by Palestinian and German terrorists at Entebbe Airport, Uganda. The rescue force—200 soldiers, jeeps, and a black Mercedes-Benz (intended to resemble Ugandan Dictator Idi Amin's vehicle of state)—was flown 2,200 nmi (2,532 mi; 4,074 km) from Israel to Entebbe by four Israeli Air Force (IAF) Hercules aircraft without mid-air refueling (on the way back, the planes refueled in Nairobi, Kenya).

During the Falklands War (Spanish: Guerra de las Malvinas) of 1982, Argentine Air Force C-130s undertook highly dangerous, daily re-supply night flights as blockade runners to the Argentine garrison on the Falkland Islands. They also performed daylight maritime survey flights. One was lost during the war. Argentina also operated two KC-130s tankers during the war, and these refueled both the Skyhawk and Navy Super Etendards which sank 6 British ships. The British also used their C-130s to support their logistical operations.

During the Gulf War of 1991 (Operation Desert Storm), the C-130 Hercules was used operationally by the US Air Force, US Navy and US Marine Corps, along with the air forces of Australia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, South Korea and the UK.

Recent history

During the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and the ongoing support of the International Security Assistance Force (Operation Enduring Freedom), the C-130 Hercules has used operationally by Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Korea, Spain, the UK and the United States.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom), the C-130 Hercules has been used operationally by Australia, the UK and the United States. After the initial invasion, C-130 operators as part of the Multinational force in Iraq used their C-130s to support their forces in Iraq.

One RAF C-130 was shot down on 30 January 2005, when an Iraqi insurgent brought it down firing with a ZU-23 anti-aircraft artillery gun while the plane was flying at 164 ft (50 m) after it had dropped SAS special forces paratroopers.[18]

A prominent C-130T aircraft is Fat Albert, the support aircraft for the US Navy Blue Angels flight demonstration team. Although Fat Albert supports a Navy squadron, it is operated by the US Marine Corps (USMC) and its crew consists solely of USMC personnel. At some air shows featuring the team, Fat Albert takes part, performing flyovers and sometimes demonstrating its jet-assisted takeoff (JATO) capabilities.

Civilian usage

The U.S. Forest Service developed the Modular Airborne FireFighting System for the C-130 in the 1970s, which allows regular aircraft to be temporarily converted to an airtanker for fighting wildfires.[19] In the late 1980s, 22 retired USAF C-130As were removed from storage at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and transferred to the U.S. Forest Service who then sold them to six private companies to be converted into airtankers (see U.S. Forest Service airtanker scandal). After one of these aircraft crashed due to wing separation in flight as a result of fatigue stress cracking, the entire fleet of C-130A airtankers was permanently grounded in 2004 (see 2002 airtanker crashes). C-130s have been used to spread chemical dispersants onto the massive oil slick in the Gulf Coast in 2010.

It was used by Pakistan Government to evacuate 150 Pakistani Citizens, mostly students from Uzbekistan during the ethnic clashes and civil unrest in June 2010.

Variants

Military variants

Significant military variants of the C-130 include:

- C-130A/B/E/F/G/H/T tactical airlifter

- C-130J Super Hercules tactical airlifter, with new engines, avionics, and updated systems

- AC-130A/E/H/U Spectre/Spooky gunship

- C-130D/D-6 ski-equipped version for snow and ice operations United States Air Force / Air National Guard

- DC-130A/E and GC-130 unmanned aerial vehicle control

- EC-130E/J Commando Solo USAF / Air National Guard psychological operations version

- EC-130E Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center (ABCCC)

- EC-130E Rivet Rider Airborne psychological warfare aircraft

- EC-130H Compass Call, electronic warfare and electronic attack.[20]

- EC-130V AEW variant used by USCG for counter-narcotics missions [21]

- HC-130N / P / P/N USAF aerial refueling tanker and combat search and rescue

- HC-130H/J USCG long-range surveillance and search and rescue

- JC-130 and NC-130 temporary and permanent conversion for flight test operations

- KC-130F/J/R/T United States Marine Corps aerial refueling tanker and tactical airlifter

- LC-130F/H/R USAF / Air National Guard ski-equipped version for Arctic and Antarctic support operations. Several examples formerly operated by the United States Navy's Antarctic Development Squadron SIX (VXE-6) in support of the National Science Foundation subsequently transferred to the Air National Guard for the same mission

- MC-130E/H Combat Talon I/II (special operations)

- MC-130W Combat Spear (special operations)[22]

- MC-130P Combat Shadow (special operations)

- YMC-130H three modified under Operation Credible Sport for second Iran hostage crisis rescue attempt

- PC-130 maritime patrol

- RC-130 reconnaissance

- SC-130 search and rescue

- TC-130 aircrew training

- VC-130 VIP transport

- WC-130A/B/E/H/J weather reconnaissance ("Hurricane Hunter") version for USAF / Air Force Reserve Command in support of the NOAA/National Weather Service's National Hurricane Center

- CC-130E/H Hercules - designation for Canadian Forces Hercules aircraft

- C-130K Hercules designation for Royal Air Force Hercules C1/C2/C3 aircraft

Operators

Operational losses

The C-130 is a reliable aircraft. The Royal Air Force recorded an accident rate of about one aircraft loss per 250,000 flying hours over the last forty years, placing it behind Vickers VC10s and Lockheed Tristars with no flying losses.[23] However, more than 15 percent of the 2,350-plus production has been lost, including 70 by the United States Air Force and the United States Marine Corps while serving in the war in Southeast Asia. By the nature of the Hercules' worldwide service, the pattern of losses provides an interesting barometer of the global hot spots over the past fifty years.[24]

Aircraft on display

- Australia

- C-130E RAAF A97-160, c/n 4160

- Airlifter with 37 Squadron from August 1966, withdrawn from use November 2000; to RAAF Museum, 14 November 2000, cocooned as of September 2005, same March 2007.[25]

- Canada

- C-130E RCAF 10315, later 130315, c/n 4070

- Service with many squadrons including 436, 435, 436 (again), 413, 8 Wing, and 426 Transport Training Squadron, by June 2005. Ground trainer, July 2006; to be installed in building, December 2007.[26]

- Norway

- C-130H Royal Norwegian Air Force 953, (USAF 68-10953) c.n. 4335

- Retired 10 June 2007 and moved to the Air Force museum at Oslo Gardermoen in May 2008.[27]

- Saudi Arabia

- C-130H RSAF 460, c/n 4566

- Operated by 4 Squadron Royal Saudi Air Force, December 1974, same January 1987. Burned on ground, air conditioner fire - in airfield corner at Jeddah, December 1989. Restored for ground training by August 1993, same March 2002. At Riyadh Air Base Museum, November 2002, restored for ground display. Tail swap with RSAF 473, c/n 5235.[28]

- United States

- C-130A USAF 55-0037, c/n 3064

- Airlifter with 773 TCS, 483 TCW, 315 AD, 374 TCW, 815 TAS, 35 TAS, 109 TAS, belly-landed at Duluth, MN., April 1973, repaired; 167 TAS, 180 TAS, to Chanute Technical Training Center as GC-130A, May 1984, same, June 1990; now displayed at Octave Chanute Aerospace Museum, Rantoul Aviation Complex, Rantoul, Illinois. as of November 1995, same, July 2006.[29]

- C-130A USAF 56-0518, c/n 3126

- Airlifter with 314 TCW, 315 AD, 41 ATS, 328 TAS; to South Vietnamese Air Force 435 Transport Squadron, November 1972; holds the C-130 record for taking off with the most personnel on board, during evacuation of SVN, 29 April 1975, with 452. Back to USAF, 185 TAS, 105 TAS; gate guard at Little Rock AFB Visitor Center by March 1993, same June 2003.[30]

- C-130A USAF 57-0453, c/n 3160

- Various airlifter assignments from 1958 to 1991, last duty with 155th TAS, 164th TAG, Tennessee Air National Guard, Memphis International Airport, Tennessee, 1976-1991, named "Nite Train to Memphis"; to AMARC in December, 1991, then sent to Texas for modification into replica of C-130A-II 56-0528, shot down by Russian fighters over Soviet Yerevan, Armenia on 2 September 1958, while on ELINT mission with loss of all crew. Now displayed in National Vigilance Park, National Security Agency grounds, Fort George Meade, Maryland. Three-blade prop replaced later four-blade version.[31]

- C-130D USAF 57-0490, c/n 3197

- Ops with 61st TCS, 17th TCS, lost no. 1 prop in flight, belly-landed, repaired, July 1975, 139th TAS with skis, July 1975-April 1983; to MASDC, 1984-1985, GC-130D ground trainer, Chanute AFB, Illinois, 1986-1990; Chanute TTC closed, September 1993, airframe to Octave Chanute Aerospace Museum, Rantoul, Illinois, July 1994; moved to Empire State Air Museum, Schenectady County Airport, New York, placed at Stratton ANGB gate, October 1994, same, August 2008.[32]

- NC-130B USAF 57-0526, c/n 3502

- Second B model manufactured, initially delivered as JC-130B; assigned to 6515th Organizational Maintenance Squadron for flight testing at Edwards AFB, California on 29 Nov 1960; turned over to 6593rd Test Squadron's Operating Location No. 1 at Edwards AFB and spent next seven years supporting Corona Program; "J" status and prefix removed from aircraft Oct 1967; transferred to 6593rd Test Squadron at Hickam AFB, Hawaii and modified for mid-air retrieval of satellites; acquired by 6514th Test Squadron at Hill AFB in Jan 1987 and used as electronic testbed and cargo transport; aircraft retired Jan 1994 with 11,000+ flight hours and moved to Hill Aerospace Museum by January 1994, same September 2008.[33]

- KC-130F USMC BuNo 149798, c/n 3680

- Used in tests in October-November 1963 by the U.S. Navy for unarrested landings and unassisted take-offs from the carrier USS Forrestal, it remains the record holder for largest aircraft to operate from a carrier flight deck, and carried the name "Look Ma, No Hook" during the tests. Retired to the National Museum of Naval Aviation, NAS Pensacola, Florida in May, 2003.[34]

- C-130G USMC BuNo 151891, c/n 3878

- Modified to EC-130G, 1966, then testbed for EC-130Q in 1981. To TC-130G in May 1990 and assigned as Blue Angels support craft, serving as "Fat Albert Airlines" from 1991 to 2002. Retired to the National Museum of Naval Aviation at NAS Pensacola, Florida, November 2002.[35]

- C-130E USAF 64-0525, c/n 4009

- On display at the 82nd Airborne Division War Memorial Museum at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Aircraft was the last assigned to the 43rd AW at Pope AFB, NC prior to retirement from the USAF.[36]

- C-130E USAF 69-6579, c/n 4354

- Ops with 61st TAS, 314th TAW, 50th AS, 61st AS; at Dyess AFB as maintenance trainer as GC-130E, March 1998, same, May 2005; to Dyess AFB museum, January 2004.[37]

- C-130E USAF 69-6580, c/n 4356

- Ops with 61st TAS, 314th TAW, 317th TAW, 314th TAW, 317th TAW, 40th AS, 41st AS, 43rd AW, center wing cracks, April 2002, to Air Mobility Command Museum, Dover AFB, 2 February 2004.[37]

- C-130E USAF 70-1269, c/n 4423

- 43rd AW, to Pope Air Park, Pope AFB, 2006.[38]

- C-130H USAF 74-1686, c/n 4669

- Airlifter with the 463rd TAW; one of three C-130H airframes modified to YMC-130H for aborted rescue attempt of Iranian hostages, Operation Credible Sport, with rocket packages blistered onto fuselage in 1980, but these were removed after mission was canceled. Subsequent duty with the 4950th Test Wing, then donated to the Robins AFB museum, Georgia, in March 1988.[39]

Specifications (C-130H)

Data from USAF C-130 Hercules fact sheet,[40] International Directory of Military Aircraft,[41] Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft,[42] Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft[43]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5 (two pilots, navigator, flight engineer and loadmaster)

- Capacity:

- 92 passengers or

- 64 airborne troops or

- 74 litter patients with 2 medical personnel or

- 6 pallets or

- 2–3 HMMWVs or

- 2 M113 armored personnel carrier

- Payload: 45,000 lb (20,000 kg)

- Length: 97 ft 9 in (29.8 m)

- Wingspan: 132 ft 7 in (40.4 m)

- Height: 38 ft 3 in (11.6 m)

- Wing area: 1,745 ft² (162.1 m²)

- Empty weight: 75,800 lb (34,400 kg)

- Useful load: 72,000 lb (33,000 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 155,000 lb (70,300 kg)

- Powerplant: 4× Allison T56-A-15 turboprops, 4,590 shp (3,430 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 320 knots (366 mph, 592 km/h) at 20,000 ft (6,060 m)

- Cruise speed: 292 kn (336 mph, 540 km/h)

- Range: 2,050 nmi (2,360 mi, 3,800 km)

- Service ceiling: 23,000 ft (7,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,830 ft/min (9.3 m/s)

- Takeoff distance: 3,586 ft (1,093 m) at 155,000 lb (70,300 kg) max gross weight;[43] 1,400 ft (427 m) at 80,000 lb (36,300 kg) gross weight[44]

Avionics

- Westinghouse Electronic Systems (now Northrop Grumman) AN/APN-241 weather and navigational radar[45]

See also

Related development

- C-130J Super Hercules

- AC-130 Spectre/Spooky

- Lockheed DC-130

- Lockheed EC-130

- Lockheed HC-130

- Lockheed LC-130

- Lockheed MC-130

- Lockheed WC-130

- Lockheed L-100 Hercules

Comparable aircraft

- Antonov An-12

- Blackburn Beverley

- Shaanxi Y-8

- Transall C-160

- Short Belfast

Related lists

- List of active Canadian military aircraft

- List of active United Kingdom military aircraft

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States (naval)

- List of aircraft of the Israeli Air Force

- List of aircraft of the Royal Air Force

- List of C-130 Hercules crashes

References

- ↑ Boyne, Walter J. (August 2004). "The Immortal Hercules" (PDF). Air Force Magazine 87 (8). http://www.airforce-magazine.com/MagazineArchive/Documents/2004/August%202004/0804herc.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ↑ Chase XCG-20 Avitruc

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rhodes, Jeff (2004). "Willis Hawkins and the Genesis of the Hercules". Code One Magazine 19 (3). http://www.codeonemagazine.com/archives/2004/articles/aug_04/hawkins/. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Boyne, Walter J. (1998). Beyond the Horizons: The Lockheed Story. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- ↑ Dabney, Joseph E. (2004). "A Mating of the Jeep, the Truck, and the Airplane" (PDF). Excerpted from HERK: Hero of the Skies in Lockheed Martin Service News (Lockheed Martin Air Mobility Support) 29 (2): 3. http://www.lockheedmartin.com/data/assets/7317.pdf. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2011 - 27th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2009. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 129.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 5.

- ↑ C-130K in the Austrian Air Force

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Stephen Trimble. "Boeing outlines C-130H and KC-10 cockpit upgrades". Flightglobal. http://www.flightglobal.com/articles/2010/06/24/343673/boeing-outlines-c-130h-and-kc-10-cockpit-upgrades.html.

- ↑ "Air Force Would Cancel Boeing C-130 Upgrade, 15 Other Programs". Bloomberg

- ↑ "Pentagon Approves C-130 AMP Production". Aviation Week, 25 June 2010.

- ↑ "Boeing C-130 Avionics Modernization Program to Enter Production". Boeing, 24 June 2010.

- ↑ "C-130 Hercules on Aircraft carrier". Defence Aviation. 2007-06-02. http://www.defenceaviation.com/2007/06/c-130-hercules-on-aircraft-carrier.html. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ↑ "USS Forrestal (CV 59)". navysite.de (Unofficial US Navy site). http://navysite.de/cvn/cv59.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Dragon Operations: Hostage Rescues in the Congo, 1964-1965, Maj. T. Odom, Combat Studies Institute, accessed January 2009

- ↑ AFSOC Heritage. US Air Force Special Operations Command. Retrieved: 31 July 2009.

- ↑ Saqib Shafi. "Pakistan Air Force - Yesterday and Today". Pakistan Military Consortium. PakDef Info. http://www.pakdef.info/pakmilitary/airforce/index.html. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ↑ "Anti-aircraft fire blamed for Iraq plane downing: report". ABC News Australia. 2005-05-17. http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2005/05/17/1370123.htm.

- ↑ "Modular Airborne FireFighting Systems". U.S. Forest Service. http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/aviation/fixed_wing/maffs/index.html. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ↑ King, Capt. Vince, Jr. (1 November 2006). "Compass Call continues to 'Jam' enemy". Air Force Link (United States Air Force). http://www.af.mil/news/story.asp?storyID=123030212.

- ↑ "Lockheed EC-130V Hercules". Military Analysis Network. Federation of American Scientists. 1998-02-10. http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/ac/ec-130v.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Housman, Damian (2006-06-29). "Highly modified C-130 ready for war on terrorism". Air Force Link (United States Air Force). http://www.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123022607. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ "Aircraft Air Accidents and Damage Rates". Defence Analytical Services Agency. http://www.dasa.mod.uk/natstats/accidents/accdam/acctab2.html. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ "Lockheed C-130 Hercules". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. 2004-11-13. http://aviation-safety.net/database/type/type.php?type=335-C. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 62.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 57.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 73.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 85.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 7.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 11.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 14.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 16.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 19.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 30.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 43.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 52.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 74.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 78.

- ↑ Olausson, Lars. Lockheed Hercules Production List 1954-2012 - 28th Edition, Såtenäs, Sweden, March 2010. Self-published. No ISBN, p. 91.

- ↑ USAF C-130 Hercules fact sheet. USAF, Ocrober 2009.

- ↑ Frawley, Gerard. The International Directory of Military Aircraft, 2002/03, p. 108. Fyshwick, ACT, Australia: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd, 2002. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- ↑ Donald, David, ed. "Lockheed C-130 Hercules". The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Barnes & Nobel Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Eden, Paul. "Lockheed C-130 Hercules". Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1904687849.

- ↑ C-130 characteristics. uscost.net. Retrieved: 7 July 2009.

- ↑ Jane's Electronic Mission Aircraft: AN/APN-241 (United States)

External links

- C-130 Hercules USAF fact sheet

- C-130 US Navy fact file and C-130 history page on Navy.mil

- C-130 page on GlobalSecurity.org

- C-130 Hercules page on AviaMil.net

- HerkyBirds.com 10,000+ C-130 images and forum

- C-130 systems on heyeng.com

- C-130 page on amcmuseum.org

- C-130 takes off and lands on a Carrier USS Forrestal at YouTube

- Newsreel footage from 1955 of blunt nose Hercules prototype at British Pathe (requires Adobe Flash)

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||